The

Atari 2600 Encyclopedia Volume 1

Author:

Derek Slaton

Publisher:

The VGA

Hardcover,

410 pages, full color, $50

Also

available via PDF ($9.99) and Apple iBooks ($12.99, both iPad and desktop Macs),

the latter of which includes gameplay footage

www.thevgatv.com

Gamers

have been cataloguing the library since at least the early 1980s.

This phenomenon kicked into overdrive during the video game fanzine explosion

of the early 1990s and the proliferation of the Internet during the mid-1990s.

Things got especially serious in 1996, when historian Leonard Herman

self-published : A

Directory of Software for the Atari 2600, a labor of love that describes

every release in encyclopedia-style form.

Now,

thanks to such platforms as Lulu and Amazon CreateSpace, self-publishing is

easier than ever, resulting in such titles as Classic 80s Home Video Games Identification & Value Guide (2008)

by Robert P. Wicker and Jason W. Brassard and The A-Z of the Atari 2600 (2013) by Justin Kyle. Works backed by

professional publishers have hit the market as well, such as my own Classic Home Video Games: 1972-1984: A

Complete Reference Guide, released by McFarland Publishers in 2007.

Enter

Derek Slaton’s The Atari 2600

Encyclopedia Volume 1, the first of a proposed four-volume series. Slaton’s

massive tome, which has the heft and binding of an oversized text book, is

gorgeous at first glance. It has a tastefully designed, shiny black cover and

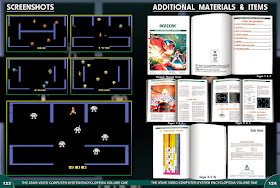

is fully illustrated throughout in full color. Each game, from Activision Decathlon to Double Dragon, has a description/review

with data (publisher, release date, etc.), complemented by such tasty visuals

as box scans, screen shots, catalogue pages, cartridges, and manuals (though

you might need a magnifying glass to read the interiors of said manuals).

Enter

Derek Slaton’s The Atari 2600

Encyclopedia Volume 1, the first of a proposed four-volume series. Slaton’s

massive tome, which has the heft and binding of an oversized text book, is

gorgeous at first glance. It has a tastefully designed, shiny black cover and

is fully illustrated throughout in full color. Each game, from Activision Decathlon to Double Dragon, has a description/review

with data (publisher, release date, etc.), complemented by such tasty visuals

as box scans, screen shots, catalogue pages, cartridges, and manuals (though

you might need a magnifying glass to read the interiors of said manuals).

Unfortunately,

upon closer inspection, the paper and printing quality come up lacking. The

book is generous in its use of colorful screenshots, but they would benefit

from glossy paper, as would the rest of the images. I assume glossy paper would

have made the book cost-prohibitive (it’s already $50 as is), so it’s hard to

blame Slaton for wanting to keep the price down to an affordable level. There

are cropping issues as well, as the text edges up too closely to the left side

on several pages.

Speaking

of the text, Slaton describes and reviews each game in a breezy, informal,

readable style and oftentimes includes humor, which is a little odd for

something called an “encyclopedia.” Slaton writes to entertain, which is fine,

but there are times when he uses humor and vague information in place of detailed

history, such as in the entry for , a.k.a. Pelé's Soccer.

Instead of explaining that was one of the first celebrities to endorse a

video game, or that most previous soccer video games were clones, Slaton writes that “there weren’t a lot of soccer

video games on the market and Pelé really wanted to endorse something, or Atari

drove up to Pelé’s front door with a dump truck full of cash.”

Each

game catalogued in The Atari 2600

Encyclopedia Volume 1 is given four pages, which is more than enough room

to include information about sequels, arcade originals, and the like, but much

of this type of history is missing. For example, nowhere in the review does it say anything

about the cartridge being a clone of Exidy’s Circus (1977) arcade game. Worse, the entry doesn’t mention Millipede

(1982), the Centipede sequel that was

ported to the Atari 2600 in 1984. Further, the chapter doesn’t mention Stargate…well, you get the idea—the book simply needs more detailed

information about each game.

Another

problem with the book is that Slaton is repetitious in expressing his opinions.

There’s an old joke about the movie reviewer who quit because he ran out of

adjectives. It appears that the same thing has happened to Slaton. For example,

he uses the word “solid” and the phrase “worth a look” way too much, sometimes

in back-to-back reviews. In addition, he should have trimmed an adverb here and

there, such as when he called Crackpots

“very solid” and the graphics for Centipede

“very underwhelming.” There’s no need for “very” in either case.

Along

the bottom first two pages of each game entry, Slaton lists such data as

publisher, release date, and genre. He also includes alternate titles. In his

review of Dark Cavern, he says that

the alternate title is Night Stalker,

but he doesn’t explain that Dark Cavern

was adapted from Night Stalker for

the Intellivision. In the Astroblast

entry, the book fails to mention that Astroblast

was adapted from Astrosmash for the

Intellivision.

On

a more nitpicky note, Slaton ends the Custer’s

Revenge (1982) chapter with: “While this is an absolutely terrible game in

terms of content and gameplay, it must be played by everyone at least once. If

for no other reason than to see the beginnings of controversy-causing video

games.” While Custer’s Revenge did

indeed raise a stink (as a pixelated General Custer, you rape an Indian woman),

“controversy-causing video games” go back at least as far as Exidy’s Death Race (1976) arcade game, which was

vilified on such programs as 60 Minutes

and in such publications as The National

Enquirer.

So

far I’ve dwelt mostly on the negatives, but there are some things I like about

the book, such as Slaton crediting obscure programmers for their work, such as

Mike Schwartz, who developed Chase the

Chuckwagon, and Robert Weatherby, who developed Chuck Norris Superkicks. Slaton also nails the appeal of certain

games, such as the “mano-a-mano” action of Combat,

which he correctly calls “one of the earliest death match games” (Midway’s Gun Fight predates Combat by two years, but the latter game is nevertheless an early

example of the genre). And, yes, I did chuckle on occasion while reading the

book.

Full

disclosure: I’ve spoken with Derek Slaton in person several times—he’s a super

nice guy with a sincere appreciation for playing classic video games, and for writing

about classic video games (he’s also the author of The Sega Master System Encyclopedia). I truly wanted to love this

book, especially when I saw the full color sample pages online. Unfortunately, it

just doesn’t merit the $50 cover price, and the title is a little deceiving. I

can live with the visuals, but there’s just not enough raw data and history,

especially given the ample space given to each game.

If

you decide to purchase the The Atari 2600

Encyclopedia Volume 1, skip the expensive hardcover version and download a

digital copy—you’ll get more value for your hard-earned dollar.